We owe a debt of gratitude to all those people who came before us in the Missions field. Their hard work has helped to set the stage that allows Mission Partners For Christ to do the work that we do. They helped to establish best practices and showed us how to properly forge healthy relationships in the communities where we do our work. Let’s take a few minutes to learn about a few of the women who came before us.

Mary Slessor, Nigeria

Mary Mitchell Slessor was born in 1848 in Aberdeen, Scotland, and grew up in the slums of Dundee. Mary was the daughter of a shoemaker. Her mother was deeply religious and made sure that Mary attended church each Sunday. Mary finished her schooling at the age of 14 when she went to work full-time at the jute mills to help support her family.

When Mary was 28, she decided to pursue her growing interest in missions. She applied to the United Presbyterian’s Foreign Mission Board in 1876 to work with them as a missionary. After a short training period in Edinburgh, Mary boarded a ship with her cousin, Robert Mitchell Beedie – who served as a missionary in Buchan – and arrived in Calabar, Nigeria in September of 1876.

Mary took the time to become fully immersed in the culture and language of her new home, which created trust and lasting relationships with the people of Calabar. She became fluent in Efik, the language of the local people. Unlike other missionaries in her time, Mary chose to live among the people to whom she ministered.

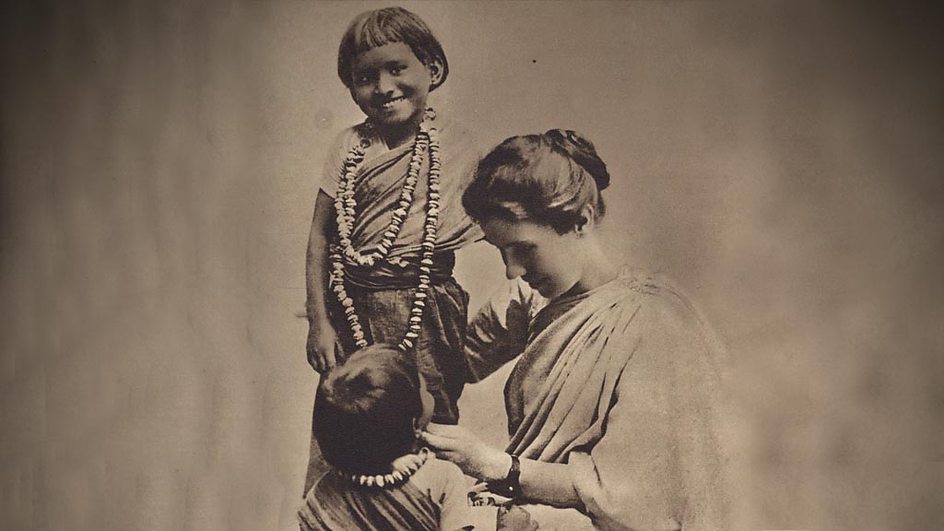

She was instrumental in ending smallpox in the region when she began a vaccination campaign amongst the local people groups in the early 1900s. She is also credited with ending the infanticide of twins, whom the Calabar people believed to be cursed and would often abandon to starve to death or to be eaten by wild animals. Mary partnered with a local mission to save as many of those babies as possible and ultimately chose to adopt many of them herself.

After multiple bouts of Malaria, Mary developed a severe fever in January 1915 and passed away. She was honored with a state funeral. Mary is remembered today in Nigeria as the “mother of all the peoples.”

Sources:

Undiscovered Scotland

Wikipedia

Wendy Grey Rogerson, Borneo

Born Rhoda Grey in Newcastle to Reverend Maurice Grey and his wife Elsie, she would grow up attending church with her family and become known as Wendy.

As a young girl growing up in a small town in England, Wendy was constantly reading books filled with tales of missionary adventures. Women like Mary Slessor and Gladys Aylward were her role models for what a young woman could accomplish. Rogerson would eventually train as a nurse, never fully suspecting that she would follow in the footsteps of the women she had admired in her childhood.

In 1948, Wendy trained as a nurse and began a career as a midwife in the Newcastle suburb known as Jesmond.

A combination of events, such as a news article she happened to read and a talk she attended, affirmed her call to the missions field. Wendy’s path was set upon learning about Borneo’s dire need for medical missionaries. She knew that Jesus was calling her to love and care for the people of Borneo. Wendy stepped foot on that island in 1959. She served as a teacher and a nurse with a mission already established in the region. Wendy was the only trained medical practitioner for hundreds of miles, and her days quickly filled with patients desperate for medical treatment.

Three years after her arrival in Borneo, Wendy took a furlough and returned to England. It was then that she met Colin Rogerson, whom she would marry. Wendy remained in England to raise her family, yet she never forgot Borneo. She returned twice in later years: once in 1985 and once in 2003.

In 2018, she published a book detailing her experiences. The book is called “The Midwife of Borneo.”

Wendy passed away in 2019 at the age of 91.

Sources:

Express

The Guardian Obituary

Christianity Today

Gladys Aylward, China

Glady Aylward was born in London, England to working-class parents, Thomas John Aylward and Rosina Florence. Gladys tried hard in school but found the work challenging. She left school to start working at age 14, eventually landing in a role as a housemaid. Four years later, through the influence of her local friends, Gladys became an Evangelical Christian.

In her late 20s, Gladys chanced upon a newspaper article that discussed the spiritual state of China. Hearing that millions of Chinese people had never heard the gospel, Gladys felt a calling to go to China as a missionary.

Gladys began training for missionary work at the China Inland Mission in London. She lasted three months before being informed by the mission’s leadership that they would not be recommending her for service due to her struggles with learning the language. Undeterred, Gladys decided that she would find her own way to China.

Having heard about an older woman, Jeannie Lawson– who served as a missionary in China and who needed a young person to assist her in her work– Gladys spent her life savings on travel fare to get to China. One October day in the early 1930s, Gladys bid her life in England farewell and began what would be a long and difficult journey to Yangcheng, China.

Gladys’s travels took her from her Liverpool station to Japan, narrowly avoiding forced labor in Russia along the way. She finally reached her destination after traveling by foot, bus, and mule and met the woman with whom she would be working. Together, they set to work to create what would be called “The Inn of the Eight Happinesses,” the name references the eight virtues: Love, Virtue, Gentleness, Tolerance, Loyalty, Truth, Beauty, and Devotion.

The Inn became a central point of their ministry. They would offer safe space to travelers and share stories with them about Jesus. A year after Gladys arrived in China, Jeannie Lawson fell and was fatally injured, leaving Gladys to run the ministry herself.

In time, Gladys began working with the government as a foot inspector. The Chinese government had passed a new law forbidding the binding of feet, a common practice in which young girls would have their feet bound to keep them small, believing that large feet were unattractive. In an era where many foot inspectors were faced with violence, Gladys’s efforts to end this cruel practice were met with success.

During her time in China, she adopted five children as her own and became the unofficial mother to hundreds more.

She eventually left China for Great Britain in 1949 when the Communist army was actively seeking out missionaries. But her heart never left China. She attempted to return after her mother’s death, but the Chinese government rejected her visa application. Instead of returning to China, Gladys moved to Taiwan in 1958 and opened the Gladys Aylward Orphanage.

She remained there until her death in 1970.

Sources:

Wikipedia

Encyclopedia.com

Dr. Ida Scudder, India

via Wikimedia Commons

It would seem that Dr. Scudder’s life path was forged for her generations before she was even born. Her grandfather, Rev. Dr. John Scudder Sr., and father, Dr. John Scudder, both served as medical missionaries. Coming from a long line of missionaries instilled Ida with a strong sense of what it means to foster a servant’s heart. She frequently witnessed illness and poverty throughout her young life.

Education was an important thing in Ida’s family. She attended seminary in Massachusetts, returning to India upon graduation to assist her father with his work. In 1894, she received a call into medical missions when three different pregnant women knocked on her door one night seeking medical assistance. Each of these women died in childbirth as they had no access to the kind of medical intervention they needed. Due to their beliefs, none of these women could be treated by men, and Ida did not have the training to help them (nor were female OB-GYNs accessible to women in that region). She had previously been adamant that she would not become a medical missionary. Still, having witnessed these terrible tragedies, she could not deny that she was called and needed to go to medical school.

Ida Scudder applied to Cornell Medical School and graduated at the top of her class – the first, of which, that accepted women. Before her return to India, a Manhattan banker known only as “Mr. Schell” decided to sponsor Ida’s ministry with a $10,000 grant in his wife’s name. Mr. Schell also ensured that Ida had all the medical instruments needed for her work in India.

Ida returned to India on January 1, 1900, and set to work immediately. Her father gave her a room for her small practice, but her needs quickly outgrew the space. By 1906, she was working with as many as 40,000 patients annually. In 1909, she opened the Mary Taber Shell Hospital.

In 1918, this doctor, who once could not envision herself working in the medical field, decided to open a medical school to train women as doctors and nurses. Expecting little interest, Ida was delightfully surprised to receive 151 applicants in her first year. She had to turn most of these applicants away, not having the resources to train so many people.

In 1928, she opened The Vellore Christian Medical Center, a larger hospital than her first. As of 2003, Vellore Christian Medical Center was the largest Christian hospital in the world.

Dr. Ida Scudder passed away in May of 1960 in her bungalow in Kodaikanal, India.

Sources:

Wikipedia

Boston University, School of Theology

The Scudder Association Foundation

Amy Carmichael, India

Amy Beatrice Carmichael, the daughter of a well-to-do flour mill owner, was born in Millisle, County Down, Ireland in 1867. She lived in an English boarding school during part of her childhood. The first few years of her life were spent in comfort, but that changed when Amy was still a young girl. Her father’s flour mill began to lose money and had to be shut down. Amy would have to leave school to help support and care for her large family.

When Amy was 16, she moved with her family to Belfast. There, Amy first felt a stirring in her soul to work with those living in poverty. She befriended a group of people known as the “shawlies”; they were so poor that they could not afford hats to protect themselves from the cold, so they covered their heads with shawls instead. Through her efforts in building relationships within the shawlie community and advocating on their behalf, she was able to build a church for them.

In 1887, Amy heard Hudson Taylor, founder of the Chinese Inland Mission, speak on missions in Asia. Then, Amy first heard her call to go overseas and preach the gospel. She applied for training and lived in London for a brief time to prepare for life as a missionary. Her health, however, prevented her from working with the Chinese Inland Mission.

She later pursued work with the Christian Missionary Society. Initially serving in Japan, Amy returned home due to poor health. However, Amy was convinced that God had called her to the mission field. She wasn’t deterred from her goals. She took the time she needed to rest and returned to work. Amy first went to Sri Lanka and finally received an assignment to the place she would call home for the next 55 years: India.

Commissioned by the Church of England’s Zenana Missionary Society, Amy found that her focus was primarily needed in ministering to women and young girls. A significant problem in India, at that time, was temple prostitution. Girls were often sold to Hindu temples by families who didn’t want daughters or needed the money; these girls were often forced into sex work to earn money for the temple priests.

In order to rescue and care for these young girls, Amy founded an orphanage in Dohnavur, where she became known as “amma” (Tamil for “mother”) and cared for hundreds of girls throughout her time in India.

In 1931, Amy suffered a nasty fall that left her bedridden, but she could not give up her work. When she couldn’t physically serve, she wrote. In her lifetime, Amy wrote close to 40 books to let the world know what God was doing through missions.

Amy Carmichael died in 1951 at the age of 83. Her body rests in Dohnavur, where she spent most of her life. Following her wishes, there is no tombstone above her grave. Instead, a birdbath has been installed and engraved with just one word: Amma.

Sources:

Christianity Today

Wikipedia

Boston University, School of Theology

Did you learn anything new about the foremothers of missions? Let us know in the comments!